You & Me On a Sunny Day

A photographer and his elderly neighbor spent every Sunday for five years making a haunting “non-motion picture” about love, loss, and breakfast.

By Rocky McCorkle

Rocky McCorkle thinks movies should be an immersive physical experience, not a disconnected visual one. “It’s one of the first ideas I ever had: to make a movie. A movie that you walk through, large-scale, almost like a movie you experience in person,” he explains.

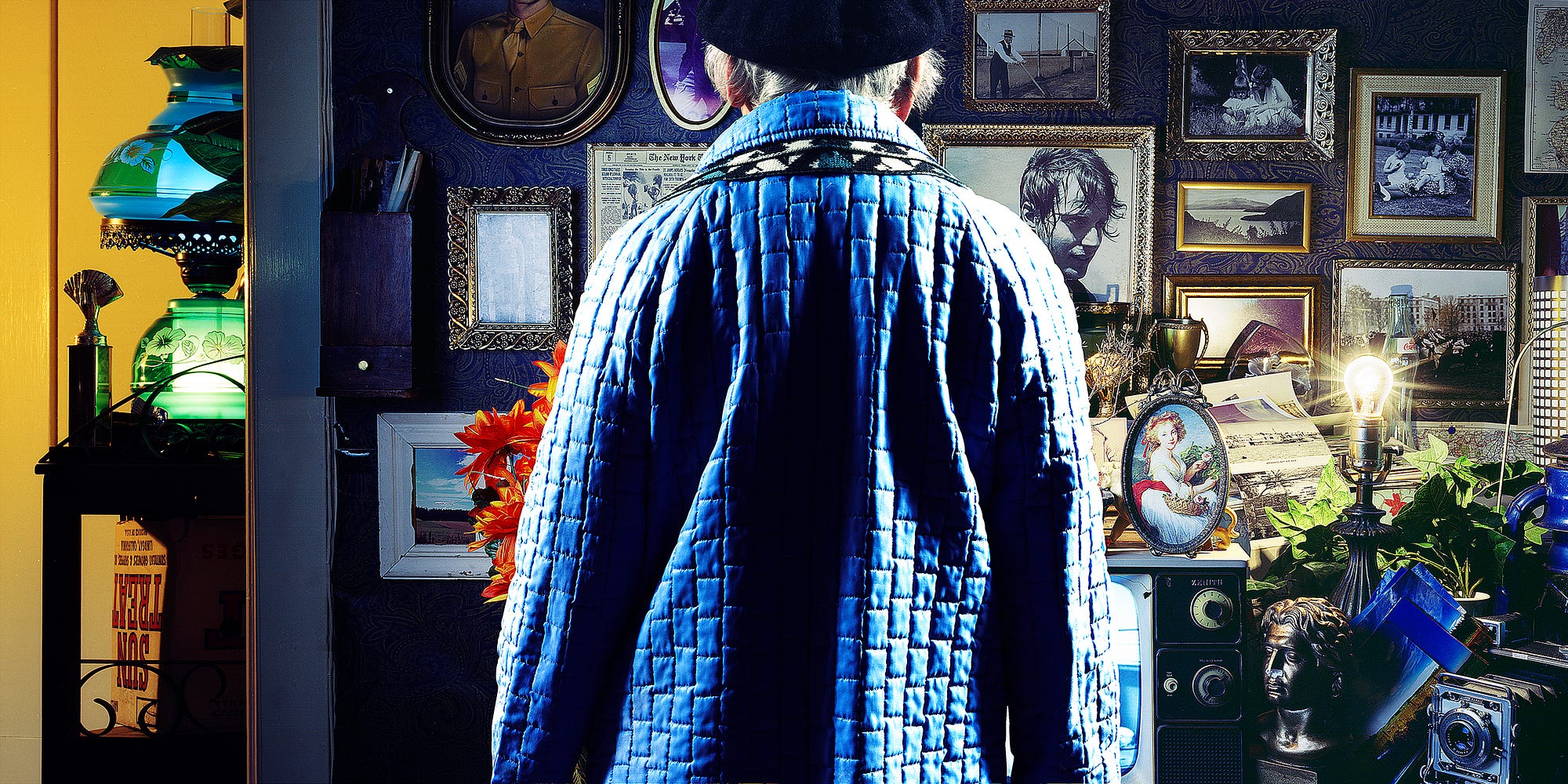

The story, inspired by the life of his own grandmother, is about an elderly woman who upon becoming a widow has vivid—almost hallucinatory—flashbacks of life with her husband. “There are times in the story as if he’s still there, she’s looking at him or talking to him,” McCorkle says of the main character, Millie, who was played by his downstairs neighbor, Gilda Todar. Todar became involved after McCorkle posted a flyer in the lobby looking for older models.“When Gilda came over, I knew she was the right one,” McCorkle says, “she was really sad when we were done, and she’s been wanting to do something else.”

But for McCorkle, good storytelling is all about the details in the setting and in the photograph. The stage was his own apartment, meticulously decorated the way he thought Millie would want it—even the trophies had the characters’ names on them—in limited colors to maintain a cohesive aesthetic. “I would buy props in that color palette of cyans, oranges, reds, and greens…I think that’s kind of the glue that holds it together,” he says. To create the images, McCorkle used a technique that merged as many as 22 angles (and therefore 22 focal points) to make the the large-format images as crisp as possible for every depth. “It’s like 40 times as much [detail] as what you’re used to seeing.”

McCorkle spent every Sunday for five years—from 2007–2012—photographing the silent film. Below is a selection of stills and captions from his non-motion picture, You & Me on a Sunny Day.

Some time ago, on a black and white morning like any other,

in continuation from yesterday,

which was in continuation from the day before, and so on, all the way back 41 or 42 years, to when our morning routine first began.

When there was a their… Now it’s just me. I continue the morning routine of eating a cinnamon-covered grapefruit because it’s become a ritual nowadays.

Jack died six days short of his 87th birthday. This is my last picture of Jack sporting his favorite hat.

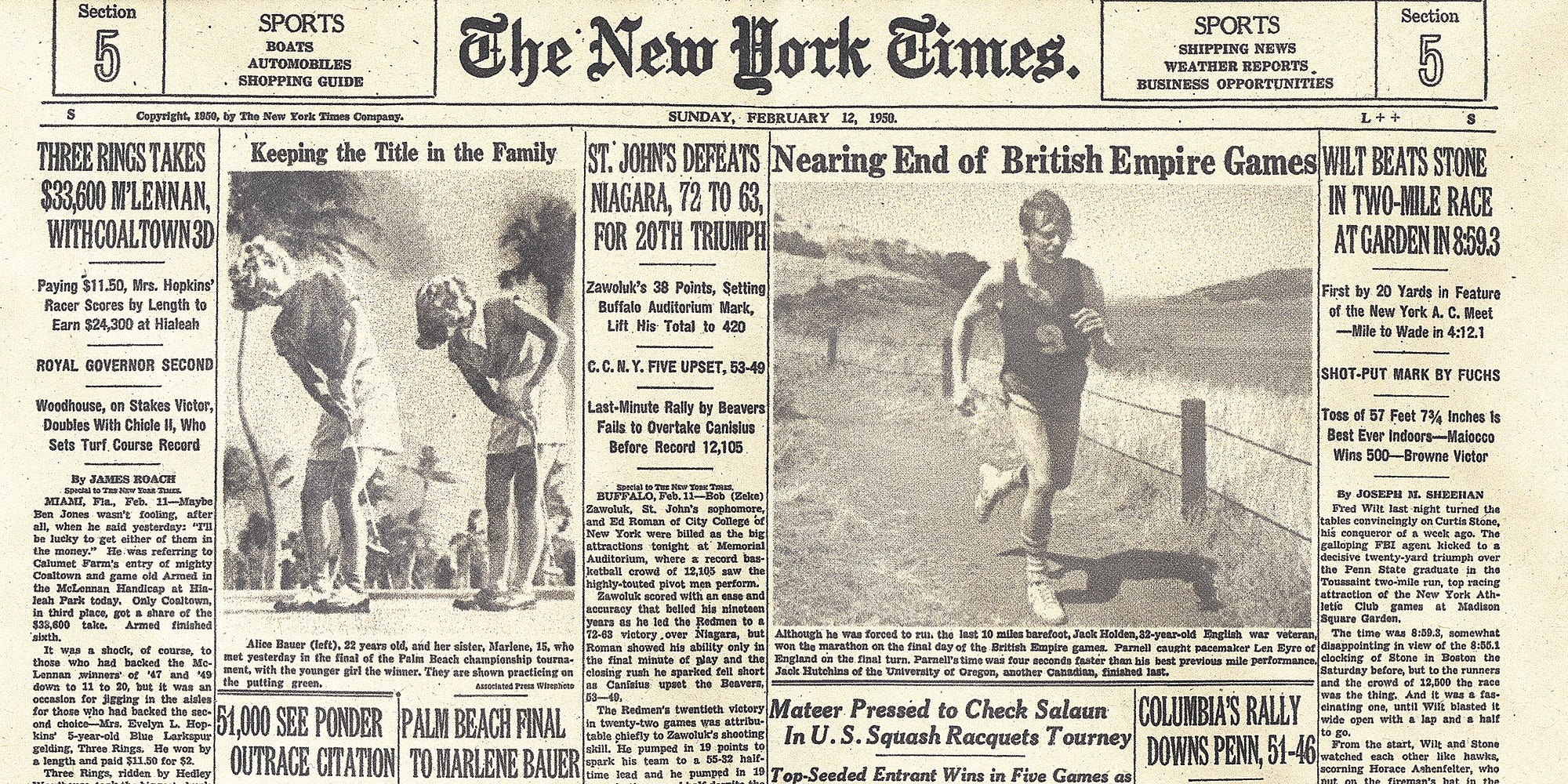

Our home became a memorabilia repository or depository or roadside memorial overflowing with a galaxy of photographs. It’s as if scenes are missing or damaged between his training in 1950 and his heart attack in 2004. I can only remember my husband as he was in pictures anymore.

I think about Jack probably seven or eight times a day. But if I’m busy at the horse track or the bingo parlor or with a little bridge game, I only think of him three or four times a day.

It must be that Hungarian filmmaker’s picture-day on TV today, a movie marathon if you will. I must have been about 29 or 30 when this movie was released. It is drafty and my mind is drifting. I rest my eyes and fall asleep.

It’s Jack, how I last remember him. He lights his cigar as a sea of sounds bounce around the living room like a public address system. For the briefest of moments, I am in two places at once.

While staring at the memorabilia, Jack’s sporting life comes rushing back to me. Running was part of his training regimen, and running eventually won out.

Jack’s day in the sun eventually came when he won the Auckland Marathon in 1950.

As if seeing with 20/20 vision, I am drawn towards the window. Young Jack grabs his yellow Converse and trademark No. 9 jersey. Then he was gone.

I feel as if I am sneaking out of the house to watch Jack run all over again. Jack is re-running through my mind. He gets farther, further, and smaller.

Comments

Post a Comment