Risky relationships: why women are more likely to die of a broken heart

In her new book, heart surgeon Dr Nikki Stamp explores how modern medicine is only beginning to understand the connection between body and emotion

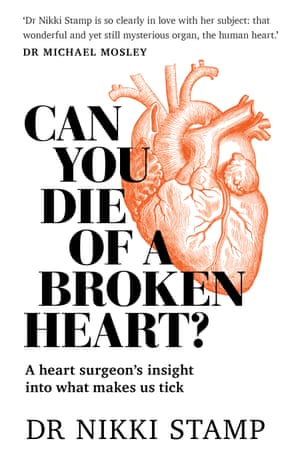

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy – commonly known as broken heart syndrome – is rare but real. As a heart and lung surgeon, Dr Nikki Stamp has seen a few cases herself, and the phenomenon provides a compelling opening chapter to her first book, Can You Die of a Broken Heart? The title reminds us of when Debbie Reynolds died “of a broken heart” the day after her daughter, Carrie Fisher, passed away in 2016, but this book rises far above the online pseudoscience accompanying those reports. It is possible to be so affected by grief or shock that a predisposed heart simply cannot cope, and Stamp uses this as an opener to explore the myriad ways modern medicine is only recently understanding (and admitting) to the connection between body and emotion.

“We’ve sort of come full circle in terms of emotion and health,” Stamp says. “When early physicians were discovering organs and the body, they actually thought the heart was the centre of emotion, because it was warm and hot and that’s where the idea of being ‘hot-blooded’ came from. And then we got kind of cold and clinical; that your emotions come from the brain, that your emotional state has nothing to do with your physical state, and now we’ve come full circle and we’re starting to encompass a more holistic view of health.”

Relationships are a great example. “There is a trend to suggest that the risk of dying is higher after the loss of someone important and close to you,” Stamp says. Conversely, she says, both romantic and platonic relationships are hugely beneficial. “There’s a lot of positive physiology and positive actions that happen in the body when you’re in a relationship. When you have social connection and emotional connection, it seems that our brains recognise that as something that means you’re healthy.”

Good hormones such as serotonin and oxytocin flood the body, preventing inflammation and assisting with blood flow.

The book doesn’t sugarcoat the risks of relationships though, and the section about divorce is sobering. One study Stamp notes in the book showed that pain centres in the brain lit up when people were shown photos of their ex-partners, and of course pain and stress have negative effects on the heart.

“It’s interesting because we’ve come to a point in culture and in society where we’re socially more accepting of divorce, yet it still has this profound effect on our health,” Stamp says. Divorce puts women under significantly more physiological strain than men, research reveals. When men remarry, their risk of heart attack drops again, but Stamp writes that, for women, divorce means a rewriting of their health prospectus forever: “The risks posed by divorce to a woman’s heart health is on a similar level to that of high blood pressure or smoking.” Men married to women, on the other hand, are significantly less likely to have heart attacks in the first place and those who do recover from them much faster than single men or women married to men.

The gendered issues inherent in heart health don’t end there either. In fact, Stamp says one of the reasons she started writing Can You Die of a Broken Heart? was because of how “scary and frustrating” it was that “women don’t identify with heart disease” despite it being the No 1 cause of death in Australian women. The book explains: “If you’re a woman under 50 years of age and you have a heart attack, then you are twice as likely to die than a man in the same boat.” Why? A contributing factor is the dearth of resources put into women’s heart health because most of the research has been done “by men, on men”.

Stamp – who is often mistaken for a nurse and referred to by her first name where her male colleagues are addressed with titles – explains that gendered issues in the industry affect medicine itself. “Women in academic medicine or even in higher levels of medical research in general are quite underrepresented. And whether we like it or not, we all have a bias towards looking at things that are more pertinent to ourselves,” she says. “So, with all of that, we’re only just now learning about both the biological and social differences between men’s and women’s hearts. And because of that, the knowledge isn’t there among healthcare practitioners, and so we don’t know what to look out for and we dismiss symptoms. Women don’t want to seem silly and then they go to their healthcare expert, a doctor or nurse, and they dismiss it as well because the symptoms are strange or because women are more likely to be perceived as being anxious. It’s just this storm of complications that mean that women’s hearts are so much more at risk.”

The most affecting thing about the book is Stamp’s infectious admiration for the organ. She describes how “breathtaking” it was the first time she saw a heart beating inside a chest as though it were love at first sight. Her book is peppered with compelling anecdotes from her professional adventures (when one patient threw a table at her, she responded, “No judgment there: grief is a nasty piece of work”). “A lot of health books seem quite prescriptive and almost paternalistic. I didn’t want to write something like that,” Stamp says. In the introduction we learn that “the very human side of what it is to care for another person” is what got her “into” medicine, and it shows. One patient’s heart surgery was put on hold so she could marry the love of her life right there in the ward. “Two days after her wedding she was wheeled down the same corridor to the operating theatre.”

Stamp admits that knowing the effect of heartbreak on her heart hasn’t made her superhuman. “At times when I was researching this book and learning about the effects of heartbreak it just sort of made me cross at the people who had broken my heart all over again,” she says, laughing, “But I think I muddle through. One of the sad inevitabilities of life is that heartbreak is going to happen to all of us at some point in time and I just hope that if and when it happens again that I do remember some of this stuff and that I might muddle my way through it just a little bit better.”

Comments

Post a Comment