What I Was Doing While You Were Reading ‘Eat, Pray, Love’

I sneered at travel memoirs where women found self-actualization through sex—because I didn’t want to admit I had lived one

I

was a bookseller when I first encountered Kristin Newman’s travel

memoir nestled among the morning delivery. Squinting for a moment, I

recognized the red blob beneath the title — What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding — as

a lipstick kiss on an airplane window. The jacket copy not only summed

up the countries she visited, but also the men she met: “Israeli

bartenders, Finnish poker players, sexy Bedouins, and Argentinean

priests.” My throat constricted, heartbeat erratic, as I slipped a copy

in my bag. I chalked up this difficulty swallowing and sweaty palms to

disagreeing with Newman’s central argument: that by travelling alone

instead of settling down, she found herself, and only then could she

walk off into the sunset she’d been destined for. I couldn’t read past

the first chapter, instead wanting to take to the streets like an

Evangelical grasping a paint paddle and duct tape sign: this book is a lie; that’s not how the story goes; repent! What I meant was: this is not how my story goes.

Five

years ago, I studied abroad in Florence, Italy, as do thousands of

students every year. While there, I had a relationship with a man, M.,

who worked in my building. When the semester ended, he disappeared and I

flew back to America. A year later, I returned alone to find him.

It’s

not uncommon for narratives of women travelling solo, like mine and

Newman’s, to run parallel to love stories. Just as often, those stories

end with the woman gaining new insight into her truest self. Perhaps

because I lived the former but was denied the latter, I resent women who

claim to have both. The only salve: proving these neat, circular

narratives false.

Essentially,

the point of entry into the country she is visiting — providing that

illuminating white space between life in the States and life abroad — is

the man, the love story. I don’t mind love, nor do I mind casual sex. I

do mind the implied assertion that foreignness of man and place are

conditions necessary for a woman’s sexual liberation that is then

equated to self-actualization. These contingencies weaken any feminist

slant narratives like Newman’s might have, since self-discovery is

seemingly accomplished only by fetishizing foreign men, an act both

dependent upon the presence of a man and reducing him to his home

country. Newman never acknowledged those Israeli bartenders, Finnish

poker players, sexy Bedouins, and Argentinean priests for what they

were: keys to cultural doors normally closed to Americans, doors that

were pivotal in leading her to that inner self. How real are insights

only won through men?

I’ve encountered iterations of this problematic trope in the obvious places: Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love, Frances Mayes’ Under the Tuscan Sun, and Gayle Forman’s fictional young adult duology Just One Day,

in which a shy college-aged girl falls in love with a European man who

disappears. I’ve even picked up and put down Jessie Chaffee’s Florence in Ecstasy

countless times. Once, I was able to work past my sympathetic nervous

system’s immediate reaction to just the title, and saw there was a

character who shared M.’s name. It’s a common Italian name, and

Chaffee’s novel grapples primarily with other themes I’m interested in,

but my stomach still rolled with nausea and I dropped the book like a

heavy stone.

Though

I never admitted it, I hoped to find myself in these stories as much as

I wanted rip the pages from their bindings. My whole life, I’ve

believed the old adage that books have the power to reflect humanity

back to their readers — making them feel less alone, seen — with

ferocity. But when I needed those books most, just the weight of one in

my hands seemed to take away something I felt to be mine.

How real are insights only won through men?

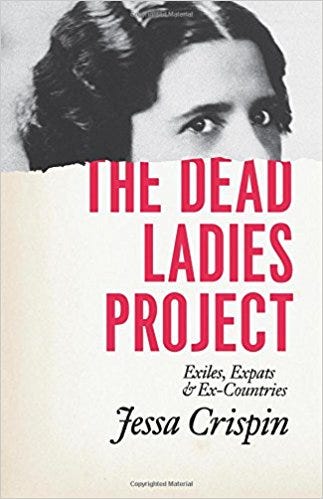

Jessa Crispin’s The Dead Ladies Project

was the only woman-traveling-solo memoir I refrained from hurling

across the room. She exists by herself through most of her time abroad,

rather than just boarding the plane alone and finding someone the day

she lands. Even so, she still asks herself: “Have I always done this,

treated men like doors rather than partners? Seeing them for what kind

of world they can take me out into, rather than their own particular

qualities?”

I wrote this on a piece of paper and hung it above my bed.

If my story was jacket copy, it would go like this:

A

series of fated accidents leads small-town Washington girl to study

abroad in Italy’s most romantic city, where she dances on tables, kisses

strange men — Brazilian bartenders, Swiss architects, Italian

doctors! — and falls in love. When her foreign lover jilts her without

explanation, she wanders lonely and lost, before ultimately flying back

to Italy to find her love — and perhaps, even herself.

In

reality, I did dance on tables and kiss Brazilian bartenders, Swiss

architects, and Italian doctors during my semester abroad. This carefree

flirt was a version of myself that didn’t exist in America, where I was

known as bookish and quiet.

Then there was M.

The

few things I knew about him starkly contrasted what I knew about

myself: he wore black on black; I always wore pink. He was in his late

twenties; I was twenty-one. He was Italian; I was American. He hated the

students I lived with; he did not hate me. In fact, as days passed, he

seemed to take an interest in me. My friends were trying to sleep with

guys in the program, while I turned those same guys down, said I’d see

them next year in America. I was different; I’d been selected.

I

don’t remember telling anyone that I hoped M. would ask me to stay,

unlike when I would come home from other dates gushing hyperbolic

accounts of midnight cityscapes and Vespa rides. Our relationship

unfolded without witnesses, early in the morning while my fellow

students slept into the afternoon. I’d emerge from my bedroom with

mussed hair and bare face, he made coffee, and we simply talked. Even

when I woke up later than usual, he stopped cleaning the dining room to

set out breakfast just for me, vinyl tablecloth sticky from the wet rag

in his hand; he compiled lists of museums, restaurants, and bars he

wanted me to visit and I carried them for days in my back pocket as

harbingers of morning conversations to come.

Though

my memory is blurred by what happens next, my few recollections of the

time right before his disappearance reflect an emotion nothing short of

awe-struck. M. saw a version of me that was at once true to but still

larger than the original, quietly bookish girl. I was sure that if he

didn’t ask me to stay, he would at least write. Our relationship was

genuine; it would exist anywhere in the world. It couldn’t end, as the

others inevitably would, with the program.

I was sure that if he didn’t ask me to stay, he would at least write. Our relationship was genuine; it would exist anywhere in the world.

But

when the semester ended, he didn’t ask me to stay, nor did he write. He

didn’t even say goodbye. I sent him frantic emails before my plane took

off, and again when it landed. He didn’t answer. As months passed and

added up into a year, M. — and the person I believed he saw me

as — calcified into myth. I disappeared with him.

When I bought a plane ticket back, my motivation was not to reclaim our relationship, but to reclaim myself. Cue sunset.

M.

learned of my return through a mutual friend before I could show up

unannounced, as the heroine of my novel quite obviously would have done.

Still, he gave me drama, left me waiting for hours at Ponte Alla

Carraia — one bridge away from the famous Ponte Vecchio, the perfect

place for a cinematic reunion. Even as he stood me up, I believed the

multiple messages he sent pleading forgiveness. I gave in to the

emotions vying for precedence over my anger and went to his apartment. I

didn’t leave for seven days.

Eventually,

I needed to pick up groceries for the room I was technically renting

across the Arno. M. recommended the store with the best prices. I said

that’s where I always went. I remember him saying something along the

lines of: Right, sometimes I forget you’ve lived here, too. He kissed me goodbye, and disappeared again.

There’s

an email address listed in the bottom right-hand corner of Jessa

Crispin’s homepage, but the domain name belongs to a website she ran

that closed in 2016. I write her only because I expect my message to sit

in an inactive inbox.

She responds.

Despite

my nerves, I try to make myself clear. Does she also see unaddressed

problems in narratives of women discovering themselves while travelling

alone — false autonomy, dehumanization of one’s partners, equating sex

to self? I don’t know how to interrogate these stories without being

misunderstood for attacking the part I agree with — a woman’s sexual

freedom.

Crispin

tells me, “Male travel writers have done this sex traveling thing for

years . . . I don’t think women doing the same things men have been

doing is any sort of progress.”

What

would constitute progress? I don’t know. I’d reclaimed neither the

relationship nor myself. M.’s second disappearance only planted more

questions, this time not of the motivation behind his repetitive

abandonment, but rather the shelf life of memory: when he will forget

me, when I will forget him, who will accomplish this Sisyphean task

first. My bet is on him.

I buy What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding again.

When

I finally finish, I email Newman, this time because I actually want a

response. I want to burrow my pain into her pithy insights; I want to

denounce her narrative with my own. But more than anything, I want my

arguments against her to be flawless.

And Newman answers.

“It

wasn’t the sex that made the difference for me; it was getting to be

brought into the local culture by a local,” she tells me. I bristle,

hoping she’ll address what I feel to be the subtext of this statement:

trading sex for cultural acceptance. I ask Newman if she thinks women

traveling alone can access this local culture without sleeping with a

local. She mentions signing up for day trips, volunteering, asking

people you don’t want to sleep with to have a drink — but ends by

saying, “People are much less motivated to make a foreign friend than

they are to have sex with a foreigner.”

Despite myself, I tell her that I agree.

Eventually

I ask about her trip to Israel, the only chapter that ends with the men

as “just an endnote.” She says, “I was going out of my way to meet

[people] because I was doing research. But only as I’m saying it to you

right now am I thinking to myself, ‘That’s how I should be going on

every single trip’ . . . I wasn’t avoiding sex, but I was going for a

different reason.”

My

heart begins its familiarly erratic dance as I realize that I’m not

angry at Kristin Newman; I’m angry at myself. I didn’t find a mirror in

Gilbert, Mayes, Forman, or even Crispin. I found a mirror in Newman, and

immediately looked away when I saw what was reflected.

Newman

refers to her abroad self as “Kristin-Adjacent”; my adjacent self was

also won through sexual liberation. I saw male attention as proof that I

wasn’t a small-town Washington girl, freshly twenty-one and always

dressed in pink. Instead, I was the woman who danced on tables and

kissed strangers. Reducing the partners I had in addition to M. served

this developing self-conception. I saw myself as worldly because men

from other countries wanted to sleep with me, not because I actually

spoke a different language or understood a culture.

I saw myself as worldly because men from other countries wanted to sleep with me, not because I actually spoke a different language or understood a culture.

Then

there’s the question of M.: was my belief that our relationship would

exist anywhere in the world accurate? Both times that we ended occurred

simultaneously with my departure from Florence, and so the two losses

not only compounded, but also became synonymous in my mind. After his

first disappearance, I confused wanting answers from him with missing

the identity I formed while abroad. He was woven into its foundations,

its stability contingent upon his presence. The immediate relief

provided by my return — to the city, to him, and therefore to

myself — only tightened the braid further.

So then, how does this story end?

So then, how does this story end?

I

could have stayed alone in Florence; I could have taught English while

becoming fluent in Italian by myself. Those choices might have resulted

in self-discovery, free from the qualifier of men providing entry.

Instead, I left.

Now

it’s four years later and I live in New York; my life — professional

and personal — is about proving books to be both mirrors and doors; I’ve

loved the same aspiring lawyer for two years. I mentally list off these

facts while standing in a bookstore where I don’t work, the weight of Florence in Ecstasy

in my hands. I’m a version of myself that’s at once true to but still

larger than who I was before, and it’s a version that doesn’t belong to

any memoirist, novelist, or even M. It belongs only to me.

My copy of What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding is tucked next to The Dead Ladies Project in

my bookshelf. I open the latter, dog-eared beyond recognition, and run

across a line I marked before, “I must take this city back from him.”

I buy another plane ticket.

Comments

Post a Comment